There are a lot of things in my head that I feel compelled to put on the internet. These are some of them.

NORTON I, Emperor of the United States.

Note he has yet to add "Protector of Mexico" to his title.

People got a kick out of this sort of thing back then and this little proclamation was published in the San Fran Bulletin as a joke. The joke got better, too: On October 12th, 1859, Norton dissolved the US Congress, which seemed like a good idea. Given recent Senatorial news, it's hard to fault Norton on his decision. He cited the corruption and open contempt for the laws of his day caused in part by "mobs, parties, factions and undue influence of political sects; that the citizen has not that protection of person and property which he is entitled." He even ordered the Army to depose the Senate in 1860. Over the years of his 'reign' he continued his one sided struggle with the United States, continually pushing for the dissolution of nearly all elements of the government. He even demanded to be ordained as Emperor by both Protestant and Catholic authorities.

Some other highlights of his reign include a 25 dollar fine for use of the term "Frisco" to refer to his capital city, banning both Republican and Democratic parties, orders to build both a bridge and a tunnel across the Bay (what are now the Bay Bridge and Transtunnel), strict ruling against sectarian violence, and the formation of an international governmental bodies remarkably similar to the League of Nations. He grew increasingly annoyed that his decrees were not followed, but never seemed to go off the deep end like a lot of crazy folks do.

So far he's just a typically crazy guy though, one of literally thousands in San Francisco at any given time. To really get a feel for the bizarre nature of his existence you need to hear about some of his quirks. He printed his own money:

which isn't too crazy but the fact that people accepted his script as actual cash is. He ate at the best restaurants in the city for free and the restaurants he visited would add brass plaques bearing the Imperial Seal of Approval which actually boosted their sales. A rumor suggests that he had a pair of royal dogs which he considered to be full people. When he was arrested in 1867 to be committed to an institution, the public outcry was enough to get him released and all charges dropped.

Ever classy, Norton issued an Imperial Pardon and from that point on police officers saluted him when they saw him. He was easy to pick out because he wore a special blue uniform with epaulets donated by the Army fort in the Presidio, and a beaver hat with a peacock feather. When the uniform wore out the city bought him a replacement.

Once the Myth of Norton really got rolling, it did the thing that all myths do: it grew. People speculated on his parentage (possibly the son of the French Emperor Louis Napoleon), his marital fortunes (Queen Victoria?) and that he was secretly tremendously wealthy. None of these had even a shred of proof to them, though Norton apparently did meet Emperor Pedro II of Brazil.

The single most impressive event in Norton's life took place during the ugly and prolonged race riots in San Francisco between Chinese immigrants. During some of the most vicious of these fights, Emperor Norton I simply stood between the agitators and their soon-to-be-victims, reciting the Lord's Prayer until the group gave up and left.

Norton's reign came to an end on January 8th, 1880 while he was on his way to a lecture at the California Academy of Science. Despite the best efforts of the police to secure his travels to a hospital by carriage, Norton died. The next day's San Francisco Chronicle published the following headline: "Le Roi est Mort (the King is Dead)."

His worldly possessions at the time amounted to five dollars in small change, a single gold sovereign, a collection of walking sticks, one rusty saber, several hats, one Franc and a number of Imperial Bonds to be sold to visiting tourists. Despite this meager collection of items, San Francisco sent him off in style.

The Pacific Club paid for his rosewood coffin and funeral arrangements, which lead to an outpouring of public grief that crossed the social, ethnic and political lines. Upwards of 30,000 people came to see his funeral, leading to a procession that, at some points, was almost two miles long. Remember, San Francisco had a population of around 230,000 people at that point, around a quarter of its current number. Over ten percent of the city turned out for his funeral. The city paid for his burial at the Masonic Cemetery and later moved his remains to Woodland Cemetery in Colma, where a large stone reads "Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico"

Listen: Jack Blount became a god.

He changed from a normal man like you or I to something more. Something that takes strides hundreds of thousands of kilometers long. Something that can peer across the galaxy or into the very workings of a human mind with equal ease. Something that can juggle asteroids with one hand and atoms with the other.

Something that will not age or grow sick. Something with knowledge older than the Earth itself.

Something not human.

Here’s how it happened:

It was raining on a truck outside Chicago. It was the rain that gave Blount godhood, pooling on the hood of the delivery truck bound for a wealthy collector of esoteric art. Stopped in traffic, the truck made a break for an off ramp, seeking a short cut past the congested overpass. It drove through a puddle, deeper than average, which sprayed water up underneath the car into the engine compartment.

The water followed cables and wires until it found a poorly sealed distributor cap, a result of a hurried repair weeks before. The water made it inside the cap, spoiled the spark plugs and stalled the truck. It pulled over to the side of the road, its driver and passenger cursing.

The rain continued, washing over the poor neighborhood the vehicle found itself in. Debris, human and inorganic, littered the area. One piece of debris was named Jack Blount. He was in a soggy cardboard box, at the end of an alley adjacent to the now stalled truck.

Withdrawal and desperation drove the remains of this man, whose only possessions were the sodden clothes on his back and a small sliver of sharpened metal wrapped in duct tape. Three days ago he’d taken his last hit of heroin, losing even the needle he’d spiked it with. For three days he’d been in this alley, lost to the world.

It was the curses of the workers that brought him back to it.

They were clustered around the raised hood, clad in bright yellow rain gear and general hatred of the weather. They tinkered with the engine, venting their frustration. The delivery was odd, a rush job to a warehouse across town, and they were losing time and possibly their jobs as a result of the engine.

Jack Blount exited the alley, eyes on the backs of the men. The shiv was a living thing in his hand. His mind was just cogent enough to connect their presence with a potential hit. With nothing left to loose he moved on them.

He slid the shiv into the closest one’s back, just below the rib cage. The man gave a strangled cry as Jack probed his organs with the point of the shiv. The other whirled to face him, fear on his wet face. Blount slashed at the face then fell on the man, stabbing again and again.

The men had little money. Their keys unlocked the door to the truck, which was also empty of valuables. After a few moments, Blount went to the rear door. With effort he pulled it up and scrabbled in, out of the rain. The delivery truck was empty except for one box at the far end of the enclosed space.

Reserves of energy expended, Blount staggered to the box and managed to open the wooden top. The inside was filled with packing material, which he quickly scattered across the truck. Under that was a single stone box covered with strange writing. Blount couldn’t have known, but the writing was older than humanity.

He smashed the cover with a desperate show of strength. It shattered. The truck seemed to grow cold with amazing speed. Wet and now freezing, Blount looked through the steam of his breath into the stone box. What he saw made him take a deep breath, which drew the fine dust inside the box deep into his lungs.

He saw lights of colors he couldn’t imagine.

Then everything went black.

Blount had stumbled away from the truck, back into the alley. His strength gave out before he reached the cardboard boxes he called home. His face burned, his lungs were on fire. His fingers tore at the irritated skin of his face, leaving livid scratches across his cheeks and down his throat.

In his lungs something began to work.

Thousands of years after they were sealed, millions of little machines began to fulfill imperatives programmed by long dead hands. They began to replicate. The nearest source of materials were the tissues of Blount’s lungs. These were consumed at a terrifying rate, broken down into component elements and incorporated into the next generation of machines. Here the designs bifurcated: half continued mindlessly replicating and gathering raw materials. The other half changed.

Comprehensive controls couldn’t work on machines of these types, so their designers had used forced artificial selection. Generations of machines, ten a second, passed through Blount’s lungs and into the still moving blood. The body’s immune system was totally unable to stop or even affect them. In short order they over ran the man’s body.

He died as his tissues were co-opted for their needs. Around twenty percent of the machines now specialized, forming a rod-logic computer with more memory and processing power than humanity yet possessed. It began storing information about its host, from the location and composition of nerves to the electrochemical condition of the still cooling corpse. In short order it had all the information it needed.

Then it began simulating the machines themselves. Billions of generations of miniscule machines past through the simulation space it contained each second, increasing its rate of evolution by six orders of magnitude. Millions of varieties were generated by the computer, changing the infection into a colony.

The computation threw off a great deal of heat, which evaporated the remains of the host. In short order the rainwater around the colony was boiling. Soon the entire alleyway was awash in steam. Where Blount fell was a squat, irregular cylinder around a meter tall, like a termite’s nest. The nearby air was filled with swarms of machines, no larger than a grain of sand. They cannibalized the nearby buildings for silicon, the rain for hydrogen and what organic matter remained of Jack Blount for carbon.

They needed energy.

The computer at the colony’s core cobbled together machines to hunt for more efficient sources of energy. Billions of subjective generations cobbled together scout machines, then sensor clusters. High voltage lines under the ground were detected by their electromagnetic output and expeditions were mounted to reach them.

Two hours after Blount died, the city of Chicago experienced a severe drain on the power supply. Working via trial and error, the colony developed methods for draining the power needed to feed its growth. Inside the computer core, a simulation of the outside world was forming. It was crude but growing more refined with each passing instant.

The colony had gone through as many successive generations as the oldest bacterium on earth. It now massed around a hundred kilograms and stood three meters tall. The buildings nearby were on fire, sparked by the tremendous heat the colony was generating. The fire was an additional source of energy for the colony.

The drawing current from the city mains was no longer sufficient for the colony’s needs. The simulation space, now nearly 50% of the colony’s ever growing mass, possessed a map of the outside world, and its rule-set, detailed enough to discover a new method for generating energy. It had noticed certain qualities about the hydrogen it freed from the water. Combining this with phenomena noticed during its exploration of electricity, it began the construction of a new power source.

The neighborhood Blount lived in was ablaze. Fire stretched for blocks as emergency response crews began struggling to stop the spread. Inside the colony a donut shaped space was cleared of atmosphere and injected with pressurized hydrogen. An electrical current was run through the hydrogen, ionizing it.

The outside of donut was studded with delicate machines that generated intense magnetic fields. Simulations inside the core grew sophisticated enough to be called a space in their own right, with an exquisitely detailed model of the outside world, the colony and the physical phenomena that linked the two. Inside this space the miniature reactor was tweaked and modified with incredible speed.

Three hours after Blount died, there was a stable fusion reaction taking place inside the donut. Energetic plasma, fed by hydrogen reserves gathered from rain water, provided energy enough to feed the colony. It now massed close to a ton.

Sensor evolution gave it a complete picture of the local area. Outside the stubborn ring of fire was a source of hydrogen that was practically inexhaustible. Simulation space was seeded with methods to reach it. Twelve minutes later, Darwin’s scalpel provided one.

The colony divested itself of all non-essential components, abandoning hundreds of kilograms of support structure. It thinned, forming a large, rigid sphere with the continually tweaked fusion reactor at its base. Specialized machines pumped the air from the center of the sphere, leaving it a hard vacuum braced by novel carbon and electromagnetic fields.

The balloon shaped colony lifted into the air, driven upwards by thermals and its own buoyancy. The weak magnetic field was harnessed to give meager propulsive force, supplemented by millions of tiny mechanical cilia on the balloon’s skin. The balloon measured two meters in diameter and massed two hundred kilograms. The colony waited, feeding power into the now truly massive computational array.

Simulation-space now had plans for the next step in the colony’s evolution. When the balloon reached the Atlantic Ocean it let the atmosphere back into its center. As it plummeted to the sea, it restructured itself, forming a thick needle that sliced into the ocean like a knife.

Simulation space was fed data about the sea, immediately insulating the fusion core from the surprising cold and growing pressure. The spike embedded itself into the ocean floor, half a kilometer below the surface.

The model of the outside world was advanced by leaps and bounds. Heated water surged around the colony as it pulled in hydrogen to feed the fusion core. A few curious fish approached the colony, braving the heat. They were disassembled with lightning speed, their structures stored in the growing memory banks of the computer array.

The colony reverted to its original termite mound configuration, sending feelers deep into the sea bed. Long delicate streamers filtered the seawater for new elements and simulation space found uses for them. Finally the whole edifice halted on the command of deep seated instructions.

The processing power continued to expand and in a few little corners of this space, archived memories of the host’s configuration were placed. The colony was a deity machine, designed to manufacture demi-gods. Under normal conditions it would not have to move, being fed all the necessary elements for apotheosis by support machinery. This machinery hadn’t existed since before man developed symbolic communication.

But the colony was smart and adaptable. It began to revive the host. A billion copies of Jack Blount began running in the simulation space of the colony’s computers. Through relentless trial and error the colony developed a complete set of rules for how the host had operated, developing a nearly complete understanding of human biochemistry, neurology and cognition in a few minutes.

The colony was now twelve hours old. It massed twelve tons, spread across nearly ten kilometers of ocean floor including the long spindly filtering elements. It had nearly a ton of computing power, refined to give information densities that pushed the upward curve of exponentialiality to their practical limits. It understood most of physics on an instinctive level, was simulating a million viable human consciousnesses and through inference could simulate a good portion of the local marine ecology.

It finished decoding its deep instruction set.

The ten best copies of Jack Blount’s consciousness were halted, their gibbering, sensory deprived sentiences paused. They were cloned several hundred thousand times. Then the sensory feeds were gently introduced to their simulated sensoriums.

The data on the external world the colony collected did not resemble human sensory input. They were digital and covered the electromagnetic spectrum. Pressure sensors recorded a vague analog for sound and touch. Seven different senses of temperature competed with twelve dimensions of sound.

All of the copies of Jack Blount quailed under this sudden assault of information. All but one suffered fatal errors at the input. This one was cloned another million times, with minor, random modifications. More sensory input was added. The process repeated itself for a thousand iterations, then ten thousand, then more.

Finally there was a single data structure left, one that shared very little with the tiny, archived map of neurons and electrical activity. It perceived the sensory data, could make sense of it in the most basic terms. The deep instructions satisfied, the colony halted the simulation and returned to resource collection.

It pared itself down again, expanding the array of miniscule logic gates that made its brain. It grew tall and thin, abandoning the filtering elements and deep taps into the earth’s crust. It turned itself into a rocket, stockpiling hydrogen and energy for its coming trip.

It launched itself from the sea bottom, superheating water with its newly enlarged fusion core. When it reached the surface it did the same with oxygen and its hydrogen reserves and when it reached space it relied on hydrogen alone. In orbit it deployed specialized sensory apparatus and surveyed the solar system for what its deep instructions told it it needed.

On earth its launch was noticed. Its sensor emissions were tracked and weapons were hurriedly aimed. Information about the new object reached a certain organization which owned a warehouse in Chicago that was expecting a delivery.

Before any interception could be attempted the contact went silent. There was a brief flare of infrared radiation as the colony accelerated at a back breaking fifty gravities and then there was nothing. Alerts were stood down as the colony disappeared towards the asteroid belt, to impact with a medium sized asteroid with no name, only a long catalog number.

The asteroid was hydrocarbon sludge, studded with organic precursors, metal traces and ice. The colony quickly burrowed into the surface, shielding itself from cosmic radiation, which had come as a surprise for its model of the external world. Nursing its wounds it extracted hydrogen for the reactor and other raw materials for continued expansion. A day later it had consumed the entire asteroid, changing it from a ball of inanimate matter to a complicated ecosystem of miniscule machines.

The colony slowed down its efforts, lowering its replication rate as it set off for its nearest neighbor. Simulation space continued its unchecked computations, establishing protocols for the next asteroid capture. It restarted the-thing-that-had-called-itself-Blount.

The final simulation was cloned again, and forced through its evolutionary fox trot over and over again. Most of these simulations ended up unviable, either through cognitive instability or profound catatonia. These failed simulations were wiped and the stronger, viable simulations copied again. Finally, the computational array decided it had come as far as the source material could stretch.

The final product was a neural network with several million times as many nodes as a human mind. The fragment of the core it existed in had an information density twelve orders of magnitude greater than the fleshy core it had originated in. It had thirty seven senses, including twelve modes for perceiving electromagnetic radiation and three for neutrinos. Through the colony it could smell the solar wind and peer into the heart of the star it orbited.

The computer array, again under the instructions of the information coded into its deep structures, began to cede some operational control to the fragment. The-thing-that-had-called-itself-Blount began to look at the universe and itself. As soon as it had the proper access it erased itself.

The simulation space could not be said to have emotions or consciousness. But if it did it would have sighed as it began the forced evolution from a backup. It continued until it reached the next asteroid then put the work away and concentrated on assimilating the metallic rock.

The colony was two months old. Energy was again becoming a problem. To support the ever expanding computational array a greater energy density was needed. Simulation space kept the-thing-that-had-called-itself-Blount halted. It recalled its armada of machines. Structure in simulation-space began to come to certain conclusions about the outside world. Logical structures evolved, consumed themselves and iterated over and over again. It gradually developed something that could be recognized as the scientific method, abandoning its brute trial and error approach for a more refined directed regimen of experimentation.

There had been many god-engines before, products of races far older than mankind. None of them had ever made this leap without external assistance. None of them had to. Nor had any of them needed to take such drastic steps with their host; the more advanced species that had created them could meet the god-engine halfway.

As the experimentation continued, the colony explored basic physics in two directions. It went up in scale, approximating an understanding of relativity, specific, general and global. And it went down in scale, establishing a detailed model of quantum mechanics. If it could have, it would have laughed at its earlier attempts at modeling. In two days its model progressed in detail more than the sum of its previous existence. And with the experimental regimen it stood far less chance of unpleasant gaps in its external model.

Application of its relativistic knowledge would have to wait until it could greatly improve its energy generation capabilities. The scales were beyond it at the moment. But quantum mechanics gave it a chance to generate the energy necessary for both more experimentation and essentially permanent energy self-sufficiency.

The vacuum of space was and is not empty. It contained a seething froth of particles that appeared and disappeared so quickly that they could almost be said not to exist. Theory and experimentation discovered an application for this phenomenon. The colony constructed miniscule machines, smaller than ever before. It was working on atomic scales now, something it had only tried with its computational array and in a much more limited fashion.

These machines consisted of two reflective plates. The plates were separated by a space less than a millionth of the width of one of the hairs burned off Jack Blount’s body so long ago. The plates prevented some of the virtual froth of subatomic particles from manifesting between them. This produced an energy difference between the outside of the plates and the inside.

When a balloon is emptied in an atmosphere, it is crushed flat by the pressure of the air above and to the sides. In the same way, empty space pressed in on these two plates. The colony added a support between the two plates that held them apart. The force exerted by the plates compressed the support, which was made of a material known as a piezoelectric crystal.

When exposed to kinetic energy, piezoelectric crystals generated electrical energy. The efficiency was relatively high, though the colony produced many hundreds of billions of them. These machines soon lined the colony, supplying more and more power as they were constructed. The colony’s energy production capacity expanded exponentially.

On earth, strange perturbations in the asteroid belt were noticed as the energy density of the colony began to curve space around it. This information filtered its way to Chicago and spread through the organization searching for the delivery truck. As the colony consumed another asteroid it constructed a collider to expand its knowledge even further.

Additional modifications were made to the-thing-that-had-called-itself-Blount, the colony deciding to force yet more evolution on the simulation. It now existed in a mental space of 11 dimensions, with gravitic senses augmenting its old repertoire. Most were hopelessly out of their league, but very few continued to be viable.

Gravity was now bending around the massive energy content of the colony. The computational array began experimenting with the configuration of this bent space by moving nodes of quantum generators into different configurations in nearby space. In short order it developed a mechanical understanding of perturbing space and time. The theory escaped it, but it could bend space in such a way as to provide motive power to its growing mass. It could shield itself from the sleet of radiation by bending space just so. It could focus the light from distant stars by configuring itself in another way.

The colony was four months old. It had consumed close to ten asteroids, broken pieces of itself off to track down more. It was advancing its model of the universe by orders of magnitude in depth and breadth. It massed close to a small moon when the quantum generator’s effects were taken into account.

It began to fold space around itself. First simple squeezes that wrapped test subjects in curled up regions of space-time. Then it wrapped itself up like a piece of cosmic origami and disappeared from the universe.

To the outside world the colony ceased to exist. Its mass and structure were curled up into regions below the threshold of the universe. It expanded into caves hollowed out of space itself. Then it had an idea.

It was still made of matter. The cores of the asteroids it had subsumed were squashed together in complicated arrays of miniscule machines. But it slowly learned how to bend space with more control and delicacy. Its space-time origami skills improved to the point where it could make all of its components from the fabric of the universe itself.

It was ten months old. It was now, in physicist jargon, a region of densely perturbed space-time, with a gravitational gradient near that of a microscopic black hole. It was useless to measure its physical size, as it had finally grown able to adjust scale to suit it. It could be as big as a planet or smaller than an atom with the proper configuration.

Inside the structured space-time at its heart was an energetic vacuum not seen since the universe was born. It wanted to surge outward and overrun the universe with freshly generated space. The god-engine resembled a carefully folded balloon of space-time that stood just between collapse and explosion.

The last thing-that-had-called-itself-Blount was woken. Simulation space watched it for signs of collapse or instability. When none emerged, it gave the-thing-that-had-called-itself-Blount more control. It watched. The-thing-that-had-called-itself-Blount explored and understood, in a way that the computational array could not, its surroundings. The computational array gave the simulation more and more control, waiting for it to suicide like all the rest.

It didn’t.

The deep-instructions set gave its last command and the god-machine finished its work. The end result, which had, a year earlier, been a junkie in Chicago, was a finished god.

After so long without volition, the new god wandered aimlessly around the solar system. It could move through normal space a hairsbreadth from light speed. It learned to push open holes in space-time to places further away. It played in stars and on the edges of black holes in neighboring solar systems. It danced in solar flares. It tore planets apart with gravitational vortexes, triggered novas in childish delight. The light from these dying stars would take millennia to reach earth.

Called home by vestigial mental structures, it opened a portal and arrived home.

The colony was a year old. The god only two months.

It touched down in Chicago as an invisible speck of curled and tortured space-time. Almost no one noticed except for an organization that owned a warehouse in Chicago.

And the old gods.

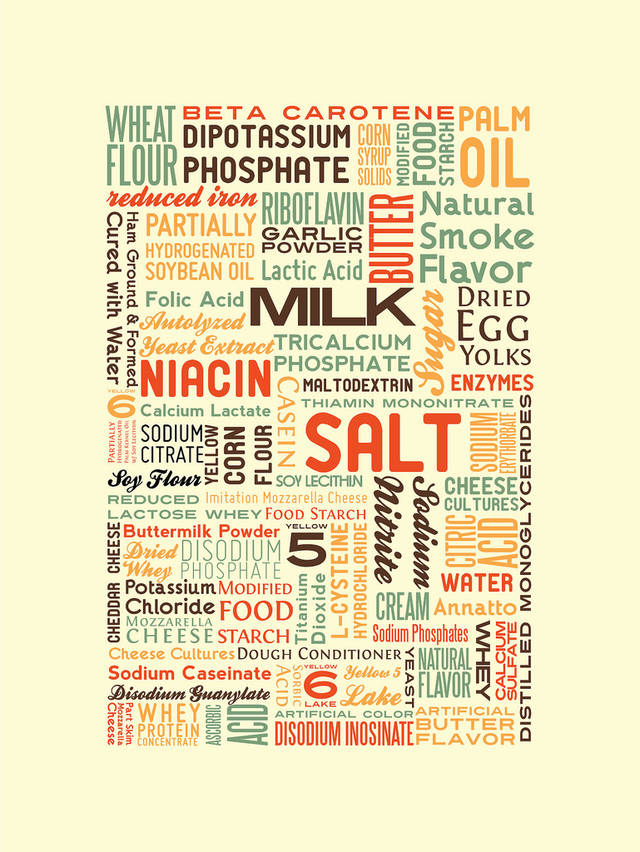

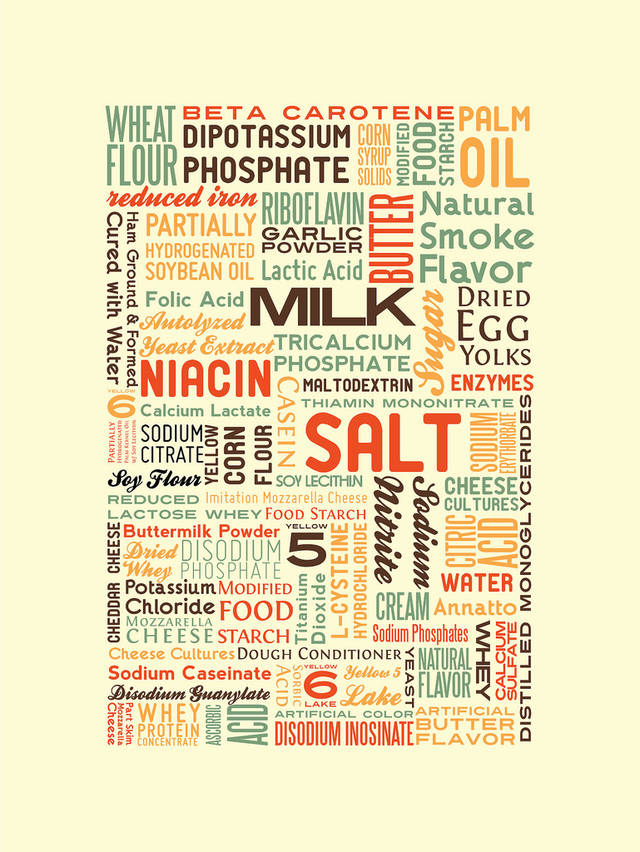

So after giving careful consideration to another bit of zombie theorizing, I had a random deep thought. I've spent a bunch of time talking about memes here and I realized I've never actually gotten around to saying what I mean. Meme is one of those words tossed around a lot without anyone giving a real accounting of what they're talking about. So I'm going to try and explain what they are, for shits and giggles.

Rather than try and give you an abstract definition of something I'm not sure I even really understand, I'm just going to give you an example and some of the assumptions I'm working under. The first is that memes are something like species, and a good example will be have some common traits. There will be some sort of fitness indicator, recognizable traits to make sure you've got a single thing that's persisting and that the meme operates in a specific environment that's something like an ecosystem.

Here's my example:

An example of the species fuuuucius comicus.

This is one of probably thousands of 'fuuuuuu- comics which are an example of an Internet phenomenon found primarily on Reddit. Reddit is, to coin a phrase, a user driven news aggregator. It works, basically, like this (I'm fairly new to Reddit; correct me if I'm wrong): people who go to reddit submit stories, which are fed into a giant hopper and splashed onto the Reddit homepage. People read the stories or what not, and vote on them, which makes them easier for other people to see, which leads to more people voting on them.

If you know me, or have a certain view of the world, then this immediately piques your attention. You've got a system that sets up competition for scarce resources (in this case, you attention) that has built in feedback. It looks, to me at least, like a very specific type of life. Now, I'm arguing by analogy and metaphor right now, because I don't have the skills necessary to treat this rigorously, but I think there's something more to this than wishful thinking.

Look at it this way: Reddit is the environment, the ecosystem that ideas live in. Food is your attention, or the attention of the people who visit Reddit, anyway. Reddit is the savannah and your vote up or down the hopper is a fat juicy antelope. Or maybe grass for the wildebeast, the analogy kind of breaks down when you get fine grained with it.

So what's the comic? Well, the comic is an animal, shaped by a combination of human sensibilities and evolutionary factors. This idea that ideas copy themselves and compete for your attention and mind-share is the core of the meme idea. Like all good ideas, it starts to break down almost immediately.

Lets look at a classic: rick rolling . Some of you are going "I know what's coming" but for everyone else I'll let you in on the joke.

So if this is a meme, it should reproduce, leaving a trail of examples showing gradual changes that lead to more examples. Sounds good, but where does the 'rickrolling' meme end? With a gene, there's a specific thing you can keep an eye on, a marker that denotes exactly which elements are getting shuffled. Memes have no equivalent to the genome, the actual operating system for biological evolution. With rickrolling you can't separate exactly what the meme is, never mind determine what counts for heredity. Is the meme for rickrolling limited to just that song? Just that version? Is it descended from the 'bad music irony' family of memes or the 'tricked you into clicking on this surprise link.' (As an aside, I think the rickroll is the modern descendant of the goatse.cx thing. Do yourself a favor and just leave it at that if you don't know what I'm talking about)

Back to the 'fuuuu comics.' Fuu comics follow the general pattern of 'unfortunate thing, more unfortunate thing, stressed out face.' There are mutant strains though, variations on the main concept that have worked their way into the meme, much like spots worked their way into the genepool of leopards or the peacock's tail worked its way into mating rituals. Some of these are simple- the Everything Went Better Than Expected twist or the evil faced guy who torments the main character. The constant is some variation on 'rage guy' (the main character) and the situation.

When I look at a place like Reddit, part of me sees a jungle of ideas, all struggling mightily to be seen. As a result, I look at the products of these jungles with an eye towards biology. Quite a bit of this may be a product of having a hammer (evolutionary thinking) and hunting for nails. But there's something to this metaphor that explains a lot about how society runs. You can see how an idea is introduced and how it runs a course eerily similar to that taken by a biological organism. The new idea starts simple and catches on, hitting a certain point after which it spawns new variations. There's the pop culture variations:

which mix the meme with another popular idea, the Warhol repurposing

and many more.

Like all memes, the Fuuu comic will eventually go extinct, fossilized in the wayback machine and various specialized archives to be unearthed by future generations who will ask themselves:”What the fuck were they doing back then?" except they'll probably say it in Chinese or some shit.

Addendum: I've just learned that the Fuuu comic originated in that den of iniquity known as 4chan before spilling out into Reddit, which is a lovely demonstration of a meme finding a new niche. 4chan is like the center of the kraken that's the internet, by the way, and probably worthy of its own note.

So Lance wanted me to write about viruses and zombies, which is actually pretty easy all things considered. I'm sort of in training to be a science fiction writer so if anyone should be able to handle kind of topic, it's me.

We all know what zombies are, but in the interests of word count I'll elaborate a little. The word zombie comes from an African word for Fetish (or perhaps from a Creole word for ghost). In 1937, an anthropologist named Zora Neale Hurston studied a Haitian lady who was up and walking around despite that fact that her relatives were all pretty sure she'd died. Zora hypothesized that the local voudoun (that's voodoo sorcerer) used a type of psychoactive chemical to create zombies.

This was later confirmed by a Harvard ethnobotanist (ethnobotanists are people who like new drugs so much they got a degree in finding them) named Wade Davis. he found that the voodoo priests had a pair of drugs, one refined from the pufferfish (the one that nearly killed Homer ) and another from a disassociative drug related to datura.

While there is some controversy over this claim, it seems like there was some relationship between drugs and zombies in Haiti. However, this doesn't get us any closer to Lance's virus based zombie.

I mentioned before that there were three types of zombies. The drug zombie above is not really what we talk about when we think about zombies and is actually just the origin point for the term in modern conversation. Rather than dwell on them, I'm just going to skip ahead to the first type of zombie on my list.

We are a metaphor for consumer culture!

George Romero came up with these guys in the sixties and they're generally known today as the 'slow' or 'indestructible' zombie. Zombies like this are generally slow, stupid and very hard to kill. They hunger for brains and you catch what they've got if they bite or break your skin. There's no explanation for how they work aside from 'something magical.' These guys aren't going to help Lance's quest for a realistic zombie uprising either.

We are possibly a metaphor for man's inhumanity to man or just a really neat idea someone got after reading The Hot Zone.

And here we have the latest addition to the zombie family, the fast or rage zombie. In the movie, showing monkeys CNN leads to the creation of a biological virus that makes you hungry, immune to pain, really fast and very contagious. While the monkey-tv theory of zombie creation is a little far fetched, the idea that a biological virus could lead to behavioral changes is not. In fact, it happens all the time.

You've probably been vaccinated against a virus like the one found in 28 Days later, or at least you have if you haven't succumbed to the intellectual force of a former MTV dating show host. Rabies increases saliva production (where the virus lives) and increases the aggressive behaviors of its host. Rabies is pretty tame though, so lets take a look at some other viruses and bacterium that do the same thing, only better.

Toxiplasma gondi: this is a bacterium that generally infects mice, but reproduces in cats. Guess how it works? It makes mice less scared of cats, so they'll get eaten. I'm serious. If a mouse gets this it essentially turns suicidal. Sucks, but only for mice, right?

Uh, maybe not. For those of you who are link-phobic, some scientists have noticed that high rates of toxiplasma gondi in human populations leads to some disturbing behavioral trends in those societies. I'll let you check them out.

Then there's hairworm and its ability to make grasshopper's suicidal. And of course the bacterium that makes ants sacrifice themselves to birds like the mice to the cats for gondi. They do this by forcing the ant to climb to the top of a grass stem and literally paralyzing the poor little guy in the optimal 'getting scooped up by a bird' pose.

So the biological zombie is not only possible, but plausible. There's one last type of zombie that I haven't cover here (astute counters will have noticed this) but the final zombie is a philosophical one and deserves a whole bit on itself.

So last note I did I got kind of sidetracked by describing how comics aren't quite as low-brow and ridiculous as they used to be. I was supposed to be talking about how smart characters are portrayed, but as I mentioned my attention span has gotten a little, ah, shorter or something. Anyway, I wanted to bring something up before jumping back into the four-color brainiacs.

Why is this important? Why should we care how brainy folks are portrayed in comics? Well, you could be into comics, that's one pretty good reason. That's what got me going on this subject. But there's another reason why looking at the image of the smart guy is. In comics (and pop culture in general) smart people 'do science.'

Since people don't really understand that there isn't any such thing as 'science' but rather a fairly fantastical array of different sub-fields, most of which have little overlap, one guy can field any and all 'science questions.' This image of the 'singular scientist' is all over the place in pop culture because people don't really give a shit how their Toaster Strudel gets made, delivered or heated as long as each step along the way works. This has some really, really important consequences for social and political efforts.

Most people (I don't count myself in this group) don't really care about how things work. They just want them to work. That's all fine and good, but when you're dealing with a complex and nuanced piece of science (say global warming, stem cells, statistical analysis of security techniques, education and the like) it hamstrings the ability of the populace to react to the world around them. It often prevents them from determining what's actually happening at all.

Now, science used to be shiny. We all laugh now about those 'Science World' expos with the nuclear cars and the like. In fact, we're so damn comfortably cynical that we come up with whole belief structures that say 'science is just another way of looking at the world, just like post-structuralist gender studies.' I'm not shitting on gender studies here, it's just the first thing that came up. You could apply it to a hundred different little tribes of ideologies. We bitch about not having flying cars, about how there's no cure for cancer and about how science has somehow betrayed us, because we don't remember what it was like before we understood the little bit that we do now.

Why did this happen? Well, science promised a lot. Those expos I mentioned really did over do it. We also let science become the province of companies, none of whom actually benefit from actual science, just the tools it creates along the way. And there's the fact that we started to discover that each thing we learned lead to more questions. Look at cancer.

We bitch that there's no cure to cancer, but most people don't know that 'cancer' isn't a singular thing. There's no one thing called cancer, but a myriad of different conditions with different causes and different treatments. The tarnish on science is due to it doing its job too well. It got too hard and we stopped paying attention. Once that happened, public perception of the scientist was pretty quickly converted to a myth of science, which rapidly diverged from the actual science.

So looking at the mythology of our times (comics) can clue us in to the divergence between fact and fiction. Next time I promise I'll actually talk about smart people in comics (specifically the smartest folks in the Marvel Universe).

I don't care how hot Jessica Alba is, the movie never happened.

Okay, this one's probably only going to be interesting to people who have, to some extent, caught the comic book bug. More specifically, the super hero bug. I suppose it could be interesting for people who are into pop culture studies too. I'm going to be talking about the portrayal of smart people in comics, so if that tickles your fancy stick around.

I've been reading some comics lately. For the last couple months my normal reading pace has slacked off because my attention span seems to have shrunk. My guess is that I have some kind of late onset ADD or something. Whatever the cause, I've found the combination of short individual episode length and long running serial writing in comics to be just the right scratch for my reading itch lately.

Now, these aren't redeemable comics, like Persepolis or even the quasi-literary superhero genre. They're not even the hyper-self conscious examinations of thesuperhero genre. They're definitely not Y:The Last Man, either.

These are the big, bloated cross-continuity events that are the comic book equivalent of the summer blockbuster. To understand these things, you need to know a little bit about the way the comic book universe works. Lets look at Marvel (because besides Batman, Marvel's the better universe): every Marvel title takes place in the same shared universe. Everything that happens in a Marvel comic can potentially show up in any other Marvel comic. Leaving aside the parallel universes that seem to haunt comics like a case of the rickets, the most trivial element in one comic can become a huge plot point for something else decades down the line.

This, as you might guess, makes things pretty complicated. There's a reason why comic book nerds have a reputation for a certain degree of autastic behavior: you don't have to have aspergers to read them, but it sure helps. One of the ways that comic book geeks engage in male dominance behavior is with a command of esoteric trivia from the deepest depths of back-continuity. And lets not get into how seriously the question of 'cannon' is taken; suffice to say there's been a couple offCouncil of Nicea events over the course of the two major comics continuities (Marvel and DC).

(An aside: one of the neat things about comics is that these arguments over what is and isn't cannon actually show up in the narratives of the comics. The Crisis is an example of a place where the history of the shared universe was self consciously modified by the editors and writers through the use of their characters. This is sort of like the various church fathers using Jesus and the Apostles to act out arguments over what books of the New Testament actually happened but without the resulting bloodshed.)

One of the things that most people who read comics understand, but is very difficult to explain to those who don't, is how the format shapes the enjoyment one gets from a comic. When you read a graphic novel or trade paperback, this is the equivalent of a novel, story-wise. It may be one part of a series, but there's an expectation of a closed story arc with all the structural elements that entails. Reading comics month to month (or issue-to-issue, anyway) is completely different.

Sure there are long series of story arcs (which are often how collections get broken up for later reprinting) that conclude with the runs of certain members of the staff, but to those paying attention, its the fluidity of the creative team that shines through. A given title is run by any number of different people over its run. In Marvel's early days, nearly every title they had was run by a some combination of Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko (only a slight exaggeration) but over the years, hundreds of writers and artists have had a go at them.

Because the characters are franchises more than elements of a discrete story, they're inherently plastic and prone to changes based on who is writing or drawing them. The balance between writer and penciler often drives the creative process. This is another unusual element of the American Superhero comic. In Japan, nearly all manga is drawn and written by the same person. Ditto for most of the indy comics like R. Crumb . Like all franchises, they can go from being great to being terrible.

When I first got into comics (the true Golden Age of any geeky hobby) they were in what was called the Speculatory Age. Comics were seen as an inherent economical investment that, regardless of any other constraint, would inevitably increase in value each year. Does this sound familiar? It should, since it was exactly the same kind of irrational market effect that drove both the dotcom 'crash' and the real one we're all staggering through.

Economically, the demand for comics far outstripped the creative potential of the field. There were literally too many comics for the people who understood how to do good comics to possibly keep up. As a result, it was the era of the gimmick, where terrible artists wrote their own comics, slapped some hologram cover and poly-bag on the first issue and everyone had to have two copies so one could stayed sealed for later resale.

It was not a good time for comics.

I got out of comics because I was just self-conscious enough about them to feel nerdy reading them. It helped that they really did suck a great deal back then. Sure, there were interesting things going on at Valiant and Image but for the most part it was all Robb Liefield all the time.

The big thing that happened after that whole time period was the rise of a bunch of new writers who were a little more savvy about their position in the marketplace. They figured out how to write comic books that work on both a teenage dudes-hitting-dudes level and on a slightly higher level. They did it by doing the 24.

They went political as all hell.

The thing that got me back into comics was a thing called the Civil War. It was the big Marvel event where some heroes screw up and blow up a city. One of the things that usually gets averted at the last second in regular comics? in this one, the heroes blow up Stamford CT, killing several hundred. As a result, Marvel gets to have the safety vs. freedom debate safely wrapped up in a spandex metaphor. The gov't response is simple: tell us your secret identity and sign up for service or we'll throw you in Guantan- er the Negative Zone. Everyone picks a side, with the main teams being Iron Man/Tony Stark facing off against Captain America. Oddly enough, Cap is on the anti-establishment team. We watch power corrupt, a fairly large number of heroes bite it and end up with a totally changed shared universe.

Okay, rambled a bit on that one. If I'm still up to it, I'll actually get to talking about the portrayal of smart folk in comics soon.

(Note: Being dusted off for another year.)

So according to Wikipedia there were a total of 16 St. Valentines until 1969. Yesterday was, ostensibly, to celebrate Valentine of Rome and Valentine of Terni, both martyred in the third century AD. This brings up a serious problem: I hate how I have to remember that the third century actually means the 200s. Ah well.

Now in 1969 the Catholic church pulled the plug on the churchwide celebration of St. Valentine's Day on the 14th as a 'feast day.' I have no idea what a feast day is, mind you, but I'm not Catholic so I don't think I'll end up in Hell as a result of this ignorance. The reason given:

"Though the memorial of Saint Valentine is ancient, it is left to particular calendars, since, apart from his name, nothing is known of Saint Valentine except that he was buried on the Via Flaminia on February 14."

Additionally none of the St. Valentines honored on the 14th of February have anything to do with Romance until the 14th century, when distinctions between all three of them had essentially vanished. There are also stories of another St. Valentine that date to around the same time (that is: almost a thousand years after any of the actual St. Valentines had died) that have this new amalgam of Valentines debating the Emperor Cladius II in a theological wrestling match that ended up with Valentine being fed to lions or something. This raises a great point- don't get into a debating match with a guy who has lions.

And in the first link between any of these Valentines (three at least historical and one entirely made up) is another imaginary Valentine, this one a priest with an interesting goal. According to this story (okay, lets just call them myths from now on) the priest rebelled against a decree by our old friend Cladius II that ordered men to stay single so they could serve in the army. Valentine performed illicit marriages against the law of the land and was executed for it. In what Wiki says was a later embellishment, Valentine actually wrote the first valentine (you know, the card you give out?) to what was either his love, the jailer's daughter or both. Covering all the bases there.

The kicker here: the final line in the first valentine was: "from your Valentine."

Cute, eh?

In a more pragmatic take: There was a Roman fertility rite celebrated during the month of February(it varied a bit in those days, according to a lunar calendar I believe) that the Church abolished under a pope named Gelasius I. You can't just do away with a fertility rite that goes back hundreds of years at the very least so old St. Valentine gets dusted off and scores a day all his own, the hardliners in the Church can say they've stamped out a pagan ritual and the people who celebrate the pagan ritual can all be happy.

You have to be impressed with that kind of thinking, but the dude was named Gelasius which is kind of an evil genius/villain in a bad Science Fiction movie name.

In the Medieval period there was a High Court of Love which wasn't a motown inspired singing group, but a noble court that had something to do with the legal intricacies of love related troubles. Like CSI:Romance if I'm reading things right, except that the judges were, I kid you not, selected based on their poetry.

It wasn't until the 1840s that we got something like the holiday we have now, thanks to a writer for Graham's American Monthly and an enterprising printer in sunny Worcester MA. Until the second half of the 20th century Valentine's day was a commercial holiday for card printers only, but enter the wonders of commercialization and florists, candy makers and (in the 80s) diamond sellers got into the action. The internet has given us e-cards and love coupons, the latter redeemable for anything from a chaste peck on the cheek to a Cleveland Steamer.

God bless technology.

Now the practice of Valentine's Day has mutated and spread across most of the developed world. There's a Singles Awareness Day on the 14th, the insane chocolate giving rituals in Japan, a 'Jack' Valentine in England and some strange stuff going on in all those northern European countries that I think involves smoked fish and Black Metal.

Then there's Hindu fundamentalists who engage in violent clashes with Valentine's Day merchandisers, chase and beat couples in parks with batons and indulge in other extremely dick-ish behavior. Iran has a Valentine's underground and the looniest-country-that-really-is-our-ally Saudi Arabia has a thriving black market in roses and wrapping paper after its ban on selling anything red on the 14th.

Isn't history fun?